If you read my first post, “A Surgeon’s Journey to the Hidden Architecture of Reality,” you’ll know I’ve been thinking deeply about how and why things feel so off in the modern world. Not just politically or scientifically—but structurally. Something feels broken. We live in a time of confusion, of contradictions, of rising noise and diminishing clarity. We sense it. We feel it. But we rarely step back far enough to ask the most important question:

How did we get here?

This isn’t just a political question, or a cultural one—it’s a question about the entire trajectory of human thought. About how we once climbed toward the light of reason, logic, beauty, and shared meaning—and then, somewhere along the way, turned back. We entered a new kind of darkness. A fog not imposed from above, but paradoxically welcomed from within.

In this piece, I’ll try to map the arc through history that has led us to this point. Not with partisan rhetoric, not with nostalgia, but with structural clarity. We will trace the rise of reason from ancient Greece, the collapse of that clarity in the Dark Ages, the rebirth of it in the Enlightenment—and then, the slow, steady unraveling that began in the mid-20th century and now permeates every layer of society.

This is the second piece in a trilogy:

What’s wrong with the world?

How did we get here?

Where do we go now?

Let’s begin where the story starts—not with collapse, but with clarity.

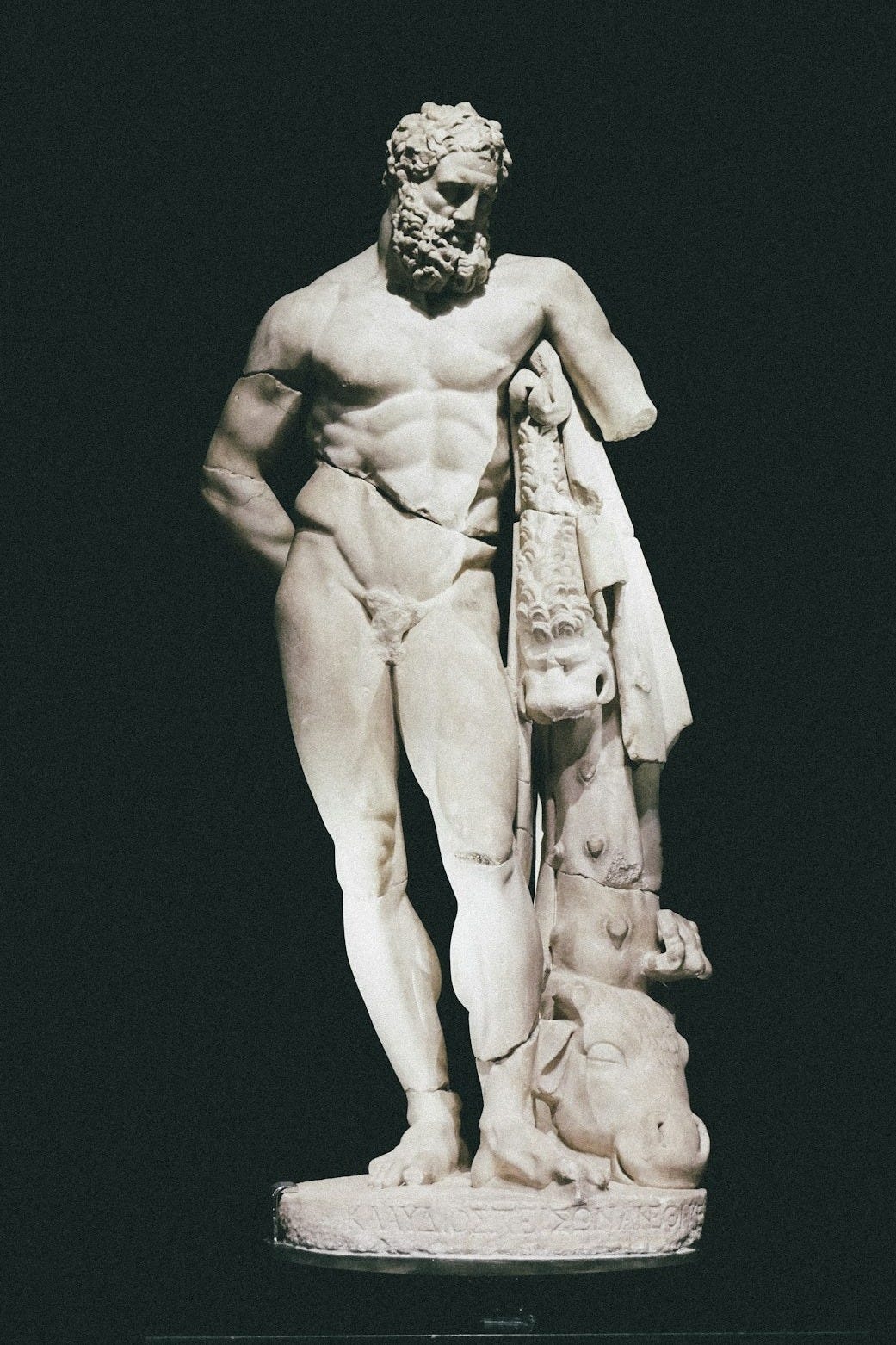

1. The Rise of Reason and Democracy

Human civilization has always been shaped by stories—but it wasn’t until ancient Greece that we began to shape those stories using reason. For the first time in history, logic was not just a tool of survival—it became a method for truth. The pre-Socratics asked what the universe was made of. Greek thinkers moved beyond that in significant ways: Socrates asked how we should live, Plato gave us the idea of eternal forms—abstract, ideal truths, and Aristotle gave us the beginnings of science and logic as structured disciplines.

But it wasn’t just intellectual, Greece also birthed a new idea: democracy. Not as we know it now—but as a radical experiment in self-governance, where citizens could participate in shaping reality through reasoned discourse. The belief behind it was profound: that if humans could reason, they could also rule themselves.

Later, Rome refined the structure. While less philosophical and more pragmatic, the Roman Republic gave us law, civic duty, and the idea that order could emerge from shared principles—not just from kings or gods.

Together, Greece and Rome created the philosophical and institutional DNA of the West. They established that truth was not just tradition, that power could be accountable, and most importantly that individuals could pursue virtue, knowledge, and a meaningful life.

It was an imperfect beginning—exclusive, elitist, and deeply flawed by modern standards. But structurally, it was revolutionary. It planted the seeds of rational civilization, where truth could be pursued, debated, and agreed upon without violence.

It would take over a thousand years for those seeds to grow again.

2. Collapse into Darkness

The fall of the Roman Empire did not simply mark the end of an era—it marked the fragmentation of truth. As Europe plunged into what we now call the Dark Ages, much of the rational structure inherited from Greece and Rome was lost, buried beneath tribal warfare, feudal hierarchies, and religious absolutism.

Reason gave way to dogma, and inquiry was replaced with obedience. The world was no longer something to understand—it was something to fear. Knowledge became the exclusive domain of religious authorities. For centuries, the ability to think freely, to question, to investigate reality—was not just discouraged, it was punished.

This was not merely an intellectual regression; it was a civilizational amnesia. The tools of logic, mathematics, science, and governance were largely forgotten in the West. In their place rose superstition, authoritarian control, and the myth of static, unchanging order.

But even then, in the shadow of lost light, the flame of reason never fully died. It was preserved—not in the cathedrals of Europe, but in the libraries of the Islamic world (who contributed themselves significantly to math and science), the scribes of monasteries, and in the oral traditions of philosophers and skeptics who whispered that something had been forgotten. That something better was once possible.

What makes this period so instructive is not just what was lost—but how long it took to even remember that it had been lost. Civilizations don’t collapse overnight. They decay slowly, as the structures of truth are eroded and replaced by authority, fear, and inertia.

That is the warning echoing through history.

3. The Reawakening: Renaissance and Enlightenment

After centuries of intellectual stillness, something stirred. In the Renaissance, Europe began to rediscover what had been lost: the works of Plato and Aristotle, the beauty of proportion, the method of logic, the belief that truth was not handed down—but uncovered. Art, science, and philosophy reawakened—not just as expressions of culture, but as tools of reality reconstruction.

This was more than an aesthetic revival. It was a civilizational correction. The Renaissance reminded humanity that the world could be studied, measured, and understood—and that individuals could reach for greatness not through obedience, but through inquiry.

From that awakening came the Enlightenment—perhaps the most structurally important movement in modern history. Thinkers like Descartes, Locke, Hume, and Kant redefined our relationship to truth. Knowledge was no longer the privilege of rulers or priests. It became the right—and responsibility—of every individual.

Governments were reimagined. Science became methodical. Ethics, liberty, and logic were placed at the center of public life. The Enlightenment did not perfect society—but it set a new trajectory: one that valued reason over superstition, debate over decree, and structure over chaos.

Most importantly, it restored the idea that truth must be pursued, not presumed.

4. The American Renaissance and Post-War Confidence

Nowhere did Enlightenment ideals take root more decisively than in the founding of the United States of America. The Constitution was not a religious text, nor a royal decree—it was a structural blueprint, forged by men who believed that liberty, law, and reason could govern a nation more justly than lineage or power ever could.

This was the first modern experiment in structured freedom. A republic—not built on bloodlines or conquest—but on the radical belief that citizens, using reason and responsibility, could guide their own destiny.

Fast-forward to the mid-20th century, and that experiment had matured. After the horrors of two world wars, something extraordinary emerged in the aftermath of World War II: a global resurgence of optimism. America became the symbol of progress through reason—a nation powered by science, technology, and an unwavering belief in human ingenuity.

The moon landing, the polio vaccine, the computer—none of these were accidents. They were the result of institutions aligned with logic, built by individuals who believed that the pursuit of truth could elevate all of humanity.

Even the culture reflected this optimism. Universities were temples of free thought. Journalism sought truth, not narrative. The public trusted scientists, doctors, engineers, and judges—not blindly, but structurally—because their authority was earned through evidence.

In physics this spirit of structured discovery soared. The early 20th century brought Einstein’s relativity, quantum mechanics, and the unification of electromagnetism—a golden age of insight that reshaped our understanding of space, time, and matter. Physicists were not mystics or cult figures; they were architects of reality, using logic and math to decode the universe. But by the late 1960s, something changed. Instead of converging toward deeper truths, the field began to fragment—retreating into abstraction, mathematical complexity, and theories detached from empirical grounding. It was a shift from clarity to cleverness, and the effects rippled far beyond physics.

This period—roughly the 1940s to early 1960s—was not perfect. But it represented the apex of rational civilization: a brief moment when knowledge, ethics, and structure moved in harmony. Even the scourge of racial segregation began to be addressed during this time, a battle that would take decades to ultimately achieve success.

And then things began to unravel.

5. The Cultural Disruption: 1960s–70s Counterculture

By the mid-20th century, the West stood atop a mountain of progress—but a storm was gathering. Beneath the surface of rational achievement, discontent was rising. The horrors of Vietnam, the trauma of assassinations, and the hypocrisy of institutional racism cracked the public trust in authority. People began to question not just the actions of power—but the very legitimacy of structure itself.

This gave birth to the counterculture—a movement that began with rightful moral outrage, but gradually mutated into something else. What started as protest against injustice became a wholesale rejection of tradition, hierarchy, and logic. Authority of any kind—intellectual, moral, or institutional—was treated with suspicion. The mantra shifted from “make it better” to “tear it down.”

At first, the impact seemed cultural: long hair, new music, psychedelic art. But the deeper shift was epistemological. Truth became subjective. Morality became relative. And what mattered was not what could be proven—but what could be felt. Reason was no longer a universal compass—it was dismissed as a tool of oppression.

Universities, once bastions of disciplined inquiry, began importing these ideas into their curricula. The seeds of postmodernism—with its distrust of metanarratives, objectivity, and logical hierarchies—took root. What had begun as a movement for civil rights and peace evolved into a philosophical rupture: a cultural rejection of the very tools that had built civilization.

Thinkers like Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, and Herbert Marcuse led this intellectual revolt. Foucault rejected objective truth, claiming that all knowledge was a mask for power. Derrida deconstructed language until words lost fixed meaning, dissolving logic into a soup of interpretation. Marcuse argued that even tolerance could be oppressive—unless it served the “right” ideology. These weren’t just academic games. Their ideas taught generations of students to distrust reason, deconstruct truth, and dismantle structure in the name of liberation. But what they offered in return was not clarity—it was confusion.

This was the moment the West began to turn not just away from its institutions—but from the principles that gave those institutions meaning.

6. The Great Fragmentation: 1980s–2000s

By the 1980s, the countercultural revolt had begun to institutionalize. The radical had become the professor. The skeptic had become the curator. And what began as a reaction to injustice devolved into an intellectual orthodoxy of deconstruction, where clarity was suspect, structure was oppressive, and truth was whatever the dominant narrative declared it to be.

In academia, postmodern critique replaced discovery. Departments that once taught history, literature, and philosophy began teaching theory—not to understand the world, but to interrogate and destabilize it. Students were no longer trained to seek truth; they were taught that truth itself was a construct, a tool of dominance to be dismantled. Even the hard sciences were not spared, as fringe movements questioned whether mathematics and physics were simply “Western constructs.”

Meanwhile, media and communication fractured. The rise of cable television, 24-hour news, and early internet forums created information silos. No longer did a population share a common set of facts, narratives, or reference points. Truth became personalized and filtered through ideological taste.

At the same time, consumerism accelerated. Culture became commodified, identity became a brand, and intellectual life was increasingly replaced with entertainment. Irony replaced authenticity, and performance replaced principle. The very idea of a shared moral or rational foundation began to disappear—not because people stopped caring, but because they no longer believed such a foundation existed.

This was not collapse by violence. It was collapse by fragmentation—a slow shattering of coherence. And once broken, structure does not reassemble itself.

7. The Digital Age and the Collapse of Trust

If the late 20th century was marked by fragmentation, the digital age amplified it into chaos. The rise of the internet promised democratized knowledge, free access to information, and a new global connectivity. But what we got instead was something else entirely: the death of shared reality.

Social media platforms, search engines, and algorithmic feeds didn’t connect us. Instead they sorted and separated us, feeding each person a custom stream of affirmation, outrage, and distraction. In this new landscape, emotion consistently outperformed logic, and virality replaced verification. What mattered wasn’t whether something was true—but whether it could generate clicks, outrage, or identity reinforcement.

This shift eroded the credibility of every institution built on trust. Science, once the gold standard of objectivity, became politicized and mistrusted. Journalism, once a guardian of public knowledge, descended into echo chamber tribal signaling and narrative shaping. Universities, once the custodians of structured thought, became battlegrounds of ideology.

The result is a kind of epistemic vertigo. People no longer agree on what is true, or even how truth should be determined. Authority is suspect, consensus is weaponized, and disagreement is viewed as threat. Everyone has a platform—but few have structure.

In this environment, conspiracy and confusion thrive. The ground has disappeared beneath our feet—not because there is no truth, but because we’ve forgotten how to recognize it.

8. Present Day: A New Dark Age

We now live in a world that appears advanced on the surface—technologically dazzling, globally interconnected—but beneath that veneer lies a profound hollowness. We have entered a new kind of Dark Age—not one of ignorance enforced by scarcity, but of confusion enabled by abundance.

The signs are everywhere:

Beauty is inverted and ugliness is celebrated as authentic, while harmony is dismissed as outdated.

Morality is politicized but not rooted in ethics, instead weaponized for tribal gain.

Language is manipulated so that words no longer mean what they used to, and deliberate ambiguity is mistaken for sophistication.

Truth is contingent not on evidence, but on the mood of the crowd.

We are told this is progress. But deep down, people sense that something has gone wrong. They feel the dissonance. They see that despite endless access to information, wisdom is vanishing. Despite mass communication, understanding is rare. And despite institutions and credentials, trust is gone.

The reason is simple: we have lost structure.

We have abandoned the very tools that built civilization—logic, coherence, shared standards of reasoning—in favor of relativism, performance, and identity. And now we wander through the ruins, mistaking the glow of our screens for the light of understanding.

This is not a collapse of infrastructure. It is a collapse of meaning.

9. A Path Forward

If you’ve made it this far, it means you already feel what many others are just beginning to sense: something foundational has broken. But unlike many voices today that only rage against the present or long for the past, this is not a call for nostalgia. It is a call for reconstruction.

We do not need to return to ancient Greece, or 18th-century salons, or mid-century America. We need to recover what made those moments powerful: the alignment of reason, structure, and moral clarity. We need to reestablish the idea that truth is not invented, but discovered. That freedom requires order. That progress without structure is not progress—it’s drift.

This series of essays is not about politics, or culture wars, or partisan alignments. It’s about the architecture beneath all of it. The structure that allows human beings to flourish—intellectually, ethically, spiritually. And yes, scientifically.

In the next essay, I’ll begin to lay out how the RTA framework—born from physics and information theory—offers not just a scientific model of reality, but a philosophical and civilizational framework for meaning itself. A way to reconnect logic with ethics, beauty with structure, and reason with purpose.

We are not helpless. We are not lost.

But first, we must remember how to see clearly again.

In the next article, we’ll begin to explore how each of us—regardless of background, belief, or profession—can help rebuild the foundation we’ve lost. Real change begins not with institutions, but with individuals who choose to think clearly, act ethically, and live with purpose.

As always, thank you for reading this article and I appreciate any feedback or ideas that you may have.